The BC NDP inherited a crisis and chose to manage its appearance rather than confront its scale

For eight years, the BC NDP has governed this province promising investments in social infrastructure, commitments to reconciliation, support for public education, and equity for marginalized communities. They positioned themselves as the progressive alternative to decades of BC Liberal austerity, the party that would finally resource schools adequately, the government that would prioritize children over corporate tax cuts.

So why are disabled children still being room cleared, still placed on partial schedules, still waiting months or years for assessments, still excluded from public education through mechanisms that operate beneath official visibility? Why are teachers still alone in classrooms with impossible ratios? Why are families still hiring private advocates to access public education? Why does every parent of a disabled child in BC know that getting your child’s basic accommodation needs met requires becoming an expert in education law, policy frameworks, and strategic escalation through bureaucratic systems designed to exhaust you into compliance?

The answer is uncomfortable: the BC NDP inherited a profoundly broken system and chose to manage the optics of that brokenness rather than confront its scale, fund its repair, or tell the truth about how long genuine transformation would require. They chose the language of “historic investments” over honest accounting of what inclusion actually costs. They chose to implement frameworks that create the appearance of accountability without enforcement mechanisms that would compel districts to change. They chose continuous improvement rhetoric over urgent intervention proportional to the harm disabled children experience daily in schools that remain under-resourced, over-capacity, and structurally hostile to neurodivergence.

This is not the same as what came before—the BC NDP has increased education funding, has acknowledged equity gaps, has created policy infrastructure the BC Liberals never bothered with. But it is also not adequate, not honest, and not remotely proportional to the crisis playing out in classrooms across this province. And the choice to position inadequacy as achievement, to treat marginal improvements as transformation, to measure success through spending announcements rather than outcomes for disabled children—that choice has consequences. It gaslights families who see the gap between government rhetoric and their children’s lived reality. It exhausts teachers who are told they have “record investments” while remaining alone with 26 students and no support. It abandons disabled children to systems that continue excluding them while reporting “progress toward strategic priorities.”

What the BC NDP inherited: Decades of manufactured crisis

To be fair—and fairness matters even in critique—the BC NDP did not create the conditions that make BC schools exclusionary and hostile to disabled children. They inherited those conditions from sixteen years of BC Liberal governance that treated education as a cost to be minimsed rather than a public good to be resourced, that stripped collective agreement language protecting class size and composition, that underfunded special education support while simultaneously moving toward “inclusive” models that placed disabled children in general education classrooms without providing the staffing or training necessary to actually include them.

The BC Liberals’ 2002 contract changes removed class size and composition limits that had prevented districts from placing unlimited numbers of high-needs students in single classrooms without adequate support. This created conditions where a teacher could be alone with 28 students, five of whom had designations requiring intensive support, with no educational assistant and no recourse. The predictable result: crisis becomes routine, room clears become classroom management tools, partial schedules become accommodation strategies, and informal exclusion becomes the pressure valve that allows the system to continue functioning at all.

The BC Liberals also systematically underfunded education while enrollment grew and complexity increased. Districts responded by cutting educational assistants, reducing specialist positions, increasing assessment wait times, and finding creative ways to exclude students whose needs exceeded available resources. The Vancouver School Board—governed by a Vision Vancouver majority through much of this period—cut spending on students with disabilities by 35% between 2016 and 2023 despite increasing designation rates, a decision that reveals how austerity logic operates regardless of nominal political affiliation.

So yes, the BC NDP inherited a crisis. Schools were already under-resourced. Teachers were already overwhelmed. Disabled children were already being excluded through partial schedules, room clears, and informal mechanisms. Assessment wait times were already measured in months or years. The infrastructure of harm was already built.

But inheritance does not determine response. What the BC NDP chose to do with that inheritance—how they narrated the problem, how they resourced the solution, how they measured progress, and most critically, how honest they were about the scale of transformation required—those were political choices. And those choices have been inadequate.

The choice: “Historic investments” or honest reckoning

The choice: “Historic investments” or honest reckoning

The BC NDP’s core political choice on education has been to emphasize spending increases while avoiding honest accounting of whether those increases are sufficient to address the scope of need, remediate decades of underfunding, or produce materially different outcomes for disabled children.

Under previous Education Minister Rachna Singh (2022-2024), the ministry regularly announced “record investments” in inclusive education. Current Minister Lisa Beare has continued this approach. Budget documents highlight year-over-year funding increases. Press releases celebrate new initiatives, pilot programs, and policy frameworks. The 2024/25 education budget included $489 million in “learning supports” funding, which the ministry describes as supporting students with diverse needs and disabilities. This sounds substantial. The ministry presents it as evidence of commitment.

But what does “record investment” mean when it’s measured against a baseline of profound inadequacy? When you’ve inherited a system that was systematically starved for sixteen years, restoring funding to barely adequate levels is not transformation—it’s triage. And when funding increases don’t keep pace with enrollment growth, inflation, and rapidly rising designation rates (which reflect both increasing identification and worsening student mental health post-pandemic), calling those increases “historic” obscures more than it reveals.

Consider what honest reckoning would require the government to say publicly:

“We inherited an education system where disabled children are routinely excluded from full-time school attendance, where teachers are unsupported in classrooms with impossible ratios, where assessment wait times make early intervention nearly impossible, and where families must become adversarial advocates to access basic accommodation. Fixing this will require sustained investment beyond current levels for at least a decade. It will require hiring thousands of additional educational assistants, school psychologists, and learning support teachers. It will require retraining the entire teaching workforce in trauma-informed, neurodiversity-affirming practices. It will require building physical infrastructure that accommodates sensory diversity. It will require tracking and dramatically reducing exclusionary practices that currently operate beneath official visibility. We are committed to this work, but we need the public to understand that continuous improvement from this baseline means disabled children will continue experiencing harm for years while we build capacity. That is unacceptable, but it is honest. And we will measure our success not by spending announcements but by outcomes: are disabled children attending school full-time? Are room clears becoming rare? Are assessment wait times measured in weeks instead of months? Are families able to access accommodation without hiring advocates?”

This is not what the BC NDP says. Instead, they say “historic investments” and “continuous improvement” and position themselves as having solved problems that families and teachers experience as ongoing and acute.

This gap between rhetoric and reality is not simply annoying—it is actively harmful. When the government claims to have made historic investments while teachers remain alone with 26 students and disabled children remain on partial schedules, families experiencing that reality feel gaslit. Are we imagining the problem? Are we ungrateful? Are we the ones being unreasonable when we say this isn’t working?

No. The problem is real. The investments remain inadequate. And the government’s choice to position inadequacy as achievement makes advocacy harder, because now families have to fight not just for resources but against the official narrative that adequate resources have already been provided.

The Framework for Enhancing Student Learning: Policy as performance

The Framework for Enhancing Student Learning, implemented in 2020, epitomises the BC NDP’s approach to education equity: create elaborate policy infrastructure that produces the appearance of accountability without enforcement mechanisms that would actually compel districts to change exclusionary practices or face consequences for failing disabled students.

The Framework requires districts to develop strategic plans, report annually on outcomes for priority populations (including disabled students), engage with communities, and demonstrate “continuous improvement.” It establishes a review process where ministry teams examine district reports and provide “capacity-building supports.” It mandates data transparency through visualizations of academic outcomes disaggregated by student population.

This sounds rigorous. It deploys the language of evidence-based decision-making, iterative improvement cycles, and equity-focused accountability. Districts must report. The ministry must review. Supports must be provided.

But notice what the Framework does not do:

- Does not establish measurable targets for reducing exclusion (no requirement that room clear rates decrease, that partial schedules become rare, that attendance gaps close)

- Does not require districts to track or report exclusionary practices (attendance, room clears, restraints, seclusion, time in segregated settings—all invisible in required reporting)

- Does not provide dedicated funding to support the improvement it demands (districts must reallocate existing inadequate resources)

- Does not establish automatic consequences when districts persistently fail disabled students (the enforcement continuum is “communicate, facilitate, cooperate, direct” where only “direct” involves compulsion, and it’s rarely used)

- Does not operate on timelines matched to childhood urgency (review cycles unfold across years while actual children experience harm in the present)

The Framework is performance management infrastructure without performance standards. It allows the government to point to policy architecture and claim they’ve created accountability, while disabled children continue being excluded and districts face no meaningful consequences for that exclusion.

This is the BC NDP’s education equity strategy in microcosm: acknowledge the problem, create the apparatus of response, avoid the enforcement and funding that would make response materially effective, then measure success by whether the apparatus exists rather than whether outcomes improve for children experiencing harm.

What truth-telling would require

If the BC NDP were committed to honest reckoning rather than optics management, here’s what they would need to acknowledge publicly:

1. The scale of exclusion is a human rights crisis, not a capacity-building opportunity

Disabled children across BC are being systematically excluded from full-time public education through mechanisms that include:

- Partial schedules that remove students from school for hours or days each week

- Room clears used as routine discipline rather than emergency safety intervention

- Chronic absence that results from schools being hostile, overwhelming, or traumatizing for neurodivergent children

- Informal “parent-requested” absences that are actually district-initiated exclusions

- Assessment wait times so long that students never receive the support they need when they need it

- IEPs that exist on paper but are not implemented due to inadequate staffing

This is not happening because educators are uncaring or incompetent. It’s happening because the system is under-resourced to the point that exclusion becomes the mechanism through which schools manage scarcity. Teachers cannot safely support a classroom of 26 students that includes multiple disabled children with intensive needs when they are alone and unsupported. So students get sent home, room cleared, placed on partial schedules—not because this is good practice, but because the alternative is teachers getting hurt and children experiencing crisis.

Framing this as a capacity-building problem—as if districts just need better strategic planning and professional development—obscures the material conditions producing harm. Districts need staff. They need enough educational assistants so teachers are not alone. They need school psychologists to reduce assessment wait times. They need learning support teachers who can provide intensive intervention. They need built environments that don’t assault sensory systems. This requires money, and the government has not provided enough of it.

2. “Historic investments” rhetoric is comparative to austerity, not adequate to need

When the government announces record education spending, they are measuring against the BC Liberal baseline—against sixteen years of systematic underfunding. Spending more than the BC Liberals spent is not the standard. The standard is: do disabled children have what they need to access education? And the answer, observably, is no.

Truth-telling would require the government to:

- Publish what adequate resourcing would actually cost (how many additional EAs, psychologists, support teachers would be needed to meet current need?)

- Acknowledge the gap between current spending and adequate resourcing

- Establish a timeline for closing that gap with measurable interim targets

- Measure success by student outcomes (attendance, inclusion, access to assessment) rather than budget announcements

3. The Framework enables accountability evasion, not accountability

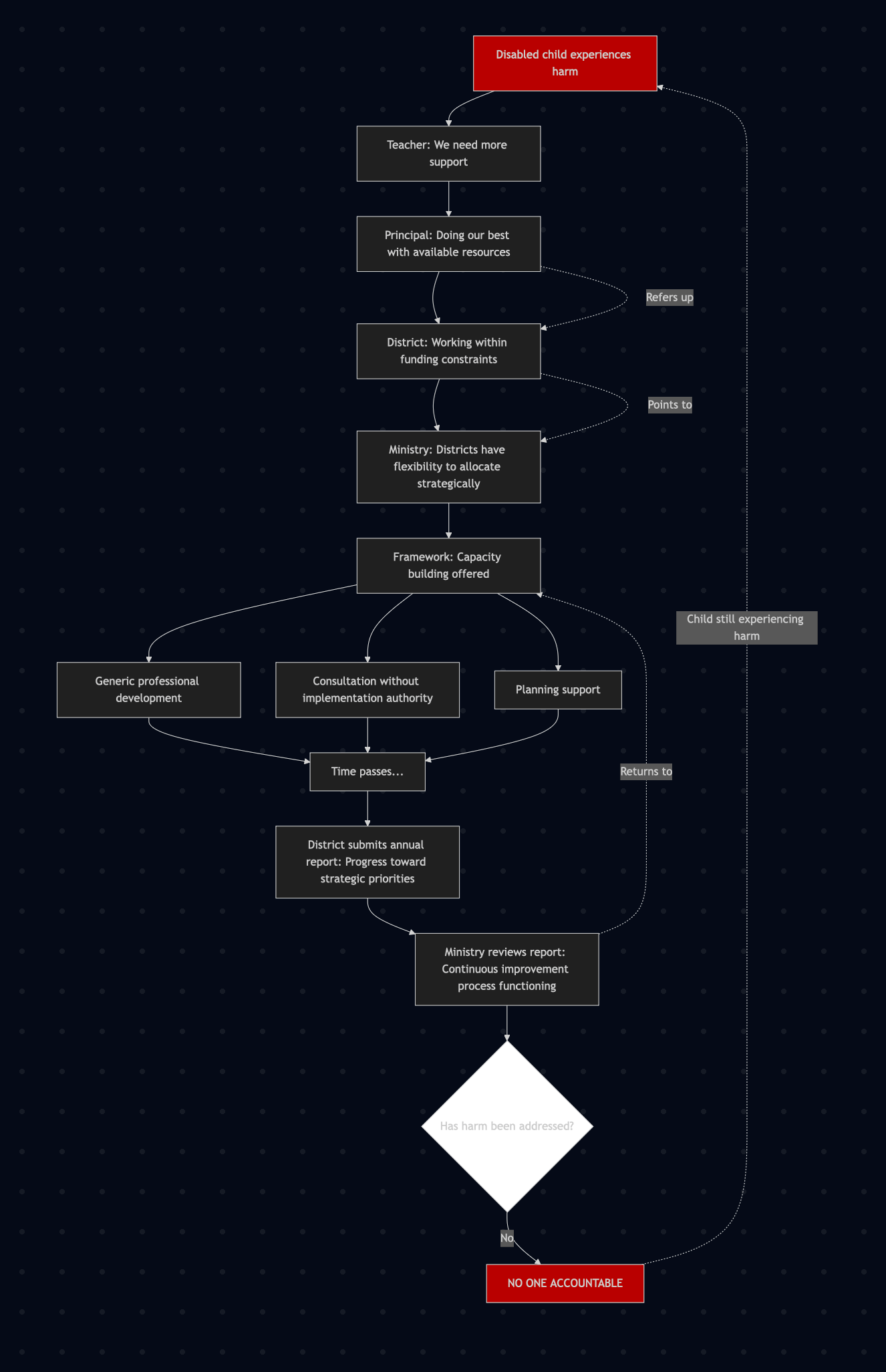

The Framework for Enhancing Student Learning allows harm to dissipate through organizational layers where no one is ultimately responsible. When a disabled child is excluded:

- Teachers say “I’m alone with 26 students”

- Principals say “The district hasn’t allocated sufficient staff”

- Districts say “We’re working within ministry funding constraints”

- The ministry says “We’ve provided resources and frameworks; implementation is district responsibility”

Everyone is responsible, so no one is responsible. The Framework institutionalizes this diffusion by requiring reporting without enforcement, demanding improvement without defining what improvement means or when it must be achieved, and measuring success through process compliance (did districts submit plans?) rather than outcomes (are disabled children receiving appropriate education?).

Truth-telling would require acknowledging that the Framework, as currently designed, cannot produce the outcomes it claims to pursue. It would require either:

- Establishing enforceable standards, measurable targets, adequate funding, and automatic consequences when districts fail, OR

- Admitting that the Framework is optics, not remedy, and that disabled children should not expect protection under its provisions

4. The political choice to avoid honesty has costs

The BC NDP has chosen to position incremental progress as transformation, to emphasize spending increases without acknowledging their insufficiency, and to create policy frameworks that manage the appearance of accountability without enforcement mechanisms that would compel change.

This choice has consequences:

It gaslights families. When the government says “historic investments” while your child is on a partial schedule, you question your own perception. Are we imagining the problem? Are we being unreasonable? This makes advocacy psychologically exhausting in ways that compound the already-exhausting work of fighting for basic accommodation.

It exhausts teachers. When educators are told they have “record resources” while remaining alone with impossible ratios, they internalize failure. If the resources are adequate and students are still in crisis, it must be my fault. I must be failing. This drives teachers out of the profession and makes burnout feel like personal inadequacy rather than systemic inevitability.

It prevents transformation. If the problem is framed as solved (we’ve made historic investments! we have accountability frameworks!), there’s no political pressure to do what would actually be required: sustained, substantial funding increases; enforceable inclusion standards; consequences for districts that exclude; honesty about timelines; measurement of success through student outcomes rather than budget rhetoric.

It abandons disabled children. Most critically, the choice to manage optics rather than confront crisis means that disabled children continue experiencing exclusion, trauma, and educational deprivation while the government reports “continuous improvement.” The children room cleared this week cannot wait for capacity-building cycles that unfold across years. They need protection now. And the government’s choice to treat urgency as if it were amenable to gradual improvement is a choice to abandon them.

What this government could do if it chose honesty over optics

The BC NDP has options. Progressive governance does not require choosing between honesty and electability. In fact, voters respect truth-telling—they understand that inherited crises cannot be solved overnight, that transformation requires sustained investment, that acknowledging scope of harm is the first step toward remedy.

Here’s what the government could do:

1. Tell the truth about scope and timeline

Conduct and publish a comprehensive needs assessment:

- How many disabled students are currently on partial schedules?

- What are current assessment wait times by district and category?

- What are current EA-to-student ratios compared to best-practice recommendations?

- What would adequate resourcing cost?

Acknowledge publicly:

- The system inherited from BC Liberals was systematically exclusionary

- Current investments, while increased, remain insufficient to meet need

- Transformation will require sustained funding beyond current levels for 10+ years

- Disabled children will continue experiencing harm during this period, which is unacceptable but honest

2. Establish enforceable standards and automatic consequences

Amend the Framework to include:

- Measurable targets: attendance equity within 3 years, room clear reduction to near-zero within 5 years, assessment wait times under 60 days within 2 years

- Mandatory reporting on exclusion: all districts must track and publish data on partial schedules, room clears, restraints, attendance by designation

- Automatic triggers: districts exceeding thresholds enter mandatory remediation with ministry oversight, financial consequences, and potential trustee appointment if persistent failure continues

- Timeline matched to urgency: quarterly monitoring, annual escalation decisions, not multi-year improvement cycles

3. Fund what’s needed, not what’s politically convenient

Commit to:

- Multi-year staffing plan to hire 5,000+ additional EAs, 500+ school psychologists, 1,000+ learning support teachers over 5 years

- Capital funding for sensory-friendly school design, quiet regulation spaces, environmental modifications

- Professional development funding for intensive, evidence-based training (not one-off workshops, but sustained coaching and implementation support)

- Family advocacy support funding so families can access information about rights without hiring private advocates

Yes, this is expensive. But honesty requires acknowledging that inclusion is expensive, that we’ve been trying to do it on the cheap, and that disabled children are paying the cost of our unwillingness to invest adequately.

4. Measure success by outcomes, not announcements

Stop announcing “historic investments” and start reporting:

- Percentage of disabled students attending full-time

- Room clear rates by district

- Assessment wait times by designation category

- Accommodation request approval/denial rates

- Chronic absence rates by designation

- Family satisfaction with accommodation process

When these metrics improve, announce progress. When they don’t, acknowledge failure and escalate response. Success is not measured by dollars spent but by whether disabled children can access education without exclusion, trauma, or family advocacy marathons.

The cost of choosing comfort over honesty

The BC NDP is not the BC Liberals. They care more about education, invest more in social infrastructure, understand that austerity logic produces harm. But caring more is not the same as caring enough. Investing more is not the same as investing adequately. Understanding harm is not the same as preventing it.

The government’s choice to position inadequate progress as achievement, to create accountability frameworks without enforcement, to emphasize spending announcements without honest reckoning of whether those dollars produce different outcomes for disabled children—these choices have consequences.

Disabled children continue being excluded. Families continue being gaslit. Teachers continue burning out. And the government continues reporting “continuous improvement” while the material conditions producing exclusion remain fundamentally unchanged.

This is not inevitable. Progressive governance could mean truth-telling about inherited crises, sustained investment matched to need, enforceable standards with consequences for failure, and success measured by whether disabled children can attend school without experiencing harm. The BC NDP has chosen a different path—one that prioritizes the appearance of accountability over the enforcement of inclusion, the rhetoric of historic investments over honest admission of continued inadequacy.

That choice is political. It could be different. And until it is, disabled children in BC will continue waiting for a government that claims to prioritize equity to actually enforce it.

What families need to know:

Your child’s exclusion is not your fault. It is not your child’s fault. It is not evidence that your expectations are unreasonable or that you’re being difficult. The system is inadequate. The government knows it’s inadequate. And they have chosen to manage the appearance of that inadequacy rather than fund and enforce the transformation required to remedy it.

Keep advocating. Keep documenting. Keep demanding better. And when the government announces historic investments, remember: investment is not the same as adequacy, frameworks are not the same as enforcement, and continuous improvement rhetoric is not the same as urgent intervention proportional to the harm your child is experiencing right now.

You are not imagining the problem. The problem is real. And it persists not because solutions are impossible but because the government has chosen incrementalism over urgency, optics over honesty, and political comfort over the protection disabled children need and deserve.