A guide to following the money from classroom crisis to courtroom settlement.

When a student gets hurt at school, when a family files a human rights complaint about exclusion, or when teachers’ unions challenge the province over underfunding—money changes hands. Lawyers get paid. Settlements get negotiated. Insurance claims get filed.

But who approves these payments? How are they recorded? And can they really tell us what they’re spending fighting to enforce scarcity in our public school system?

The answer lies in British Columbia’s Corporate Accounting System—a detailed financial tracking system that codes every government payment, including legal fees and settlements. The province knows exactly what it spends. It just fragments the information across multiple streams to make the total invisible.

This matters because these costs come directly from education budgets. Every dollar spent fighting families in court is a dollar that didn’t go to hiring educational assistants, reducing class sizes, or providing specialised supports. Understanding how these payments flow through government accounts reveals not just what BC spends on legal defence—but what it chooses not to spend on students.

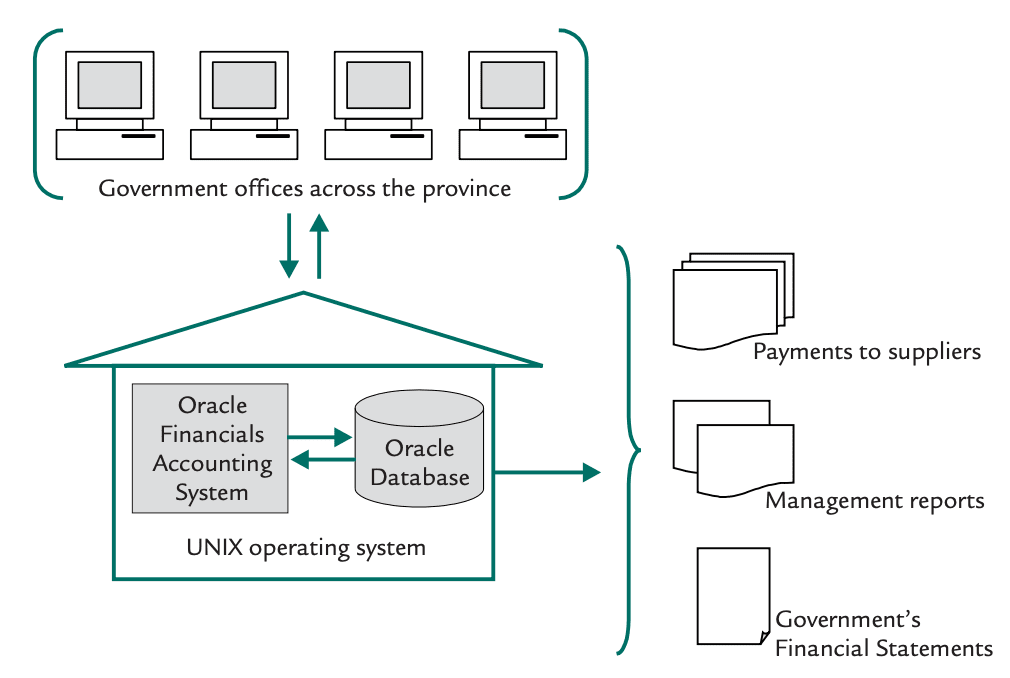

How government payments get tracked

Every payment the BC government makes—whether to a law firm, an insurance company, or a family settling a claim—flows through the Corporate Accounting System (CAS).

What it doesn’t show is the humans involved. This is a structured database that requires every transaction to be coded with specific information. For a cost to be paid, a human must code each transaction according to these considerations:

- Client: Which ministry (e.g., Education and Child Care)

- Responsibility centre: Which division or branch

- Service line: Which program or activity

- STOB code: What type of expense (the critical piece)

- Project code: Specific initiative if applicable

- Location code: Geographic area if relevant

- Future: Reserved for additional classification

The structure of this system is detailed in a 2006 Auditor General report on the Corporate Accounting System, which explains how each segment classifies government transactions.

The STOB code (Standard Object of Expenditure) is what classifies spending by type. Legal fees typically get coded as STOB 60 (Professional Services – Operational & Regulatory) or STOB 61 (Professional Services – Advisory). These are the same codes flagged in BC’s “Directive 07-2016: Disclosure of Professional Services Contracts” requiring public disclosure of professional services contracts over $25,000.

A 2024-25 internal audit on financial risk assessment found that confusion over professional services coding is common, with auditors noting cases where legal contracts were misclassified under the wrong STOB or category.

“While most contract data is correctly recorded, and staff are knowledgeable, we observed gaps in formal training, STOB classification guidance, and documentation practices. These lead to an inconsistent understanding and application of data policies across ministries”

When the Ministry of Education pays a law firm, accounts payable staff must enter the transaction into CAS with all these codes, plus a brief narrative description—usually the invoice details or claim reference number. The payment then requires approval from division managers and Chief Financial Officer sign-off for significant amounts.

The provincial financial system is designed to record every payment in detail.

What is far less clear is whether this information is routinely aggregated or reported in a way that allows the public—or even decision-makers—to see the total cost of education-related legal disputes across ministries, insurance programs, and internal legal services. Public reporting does not currently provide a consolidated picture of these costs, even though the underlying transactions are recorded.

Three streams where legal costs flow

Education legal costs don’t show up in one place. They’re fragmented across three separate accounting streams, each managed by different entities:

Direct Ministry payments

When the Ministry of Education and Child Care hires external lawyers—firms like Harris & Company, Fasken Martineau, or Harper Grey—those invoices come through the ministry’s accounts payable. Staff code them with the appropriate STOB (60 or 61 for legal services), assign them to the relevant division, and process payment.

These show up in the ministry’s operating expenses under categories like “Professional Services” or “Other Suppliers.” But you won’t find a line item labeled “legal costs for fighting families.” The spending is real, coded, and tracked—it’s just buried in aggregate categories.

Example: In 2023-24, Vancouver School Board paid approximately $3.2 million to Harris & Company alone for labour and litigation advice. Analysis of the VSB’s 2024-25 budget documents shows the board explicitly allocates $7.66 million for legal and litigation costs—money the board itself admits “could have gone into classrooms.”

Insurance and Settlement Costs

Most people miss this stream entirely. When school districts face liability claims—student injuries, discrimination complaints, human rights cases—many are covered by the School Protection Program (SPP), run by the Ministry of Finance’s Risk Management Branch.

Here’s how it works:

When an incident occurs → School district files a claim with SPP → Risk Management assesses liability → If valid, SPP negotiates settlement or defends in court → Payment comes from the insurance fund.

The accounting gets complicated. Sometimes SPP pays the claimant directly, and the district records a journal voucher (internal transfer) charging its budget and crediting the SPP fund. Other times the district pays first, then gets reimbursed through another journal entry. Either way, the transaction appears in CAS—but it looks like an internal allocation, not an obvious “legal settlement” expense.

What SPP covers:

- Student injuries and third-party claims

- Liability for authorized school activities

- Legal defence costs for covered claims

What SPP doesn’t cover:

- Employee workplace injuries (that’s WorkSafeBC, a separate system)

- Criminal acts or intentional harm

- Claims falling outside authorised activities

The School Protection Program policy documents outline this coverage structure in detail, noting that “SPP liability coverage is specifically excluded for criminal or illegal acts.”

Example: School District 57 (Prince George) paid a $1.1 million settlement in 2022 to a man who suffered sexual abuse as a student in the 1980s. The district’s insurer covered it—meaning the money came from SPP, not the district’s operating budget. But the cost ultimately flows back through insurance premiums and provincial allocations. The money is public money. It’s just routed through insurance to obscure the total.

Attorney general cost allocation

When legal work is handled by the province’s central legal services (the Attorney General’s in-house lawyers) rather than external counsel, those costs get allocated back to the requesting ministry through internal billing.

The Attorney General doesn’t send Education an invoice like an external law firm would. Instead, they use journal vouchers to charge back costs—staff time, litigation expenses, shared resources. These appear in CAS as cost recoveries or inter-ministry transfers.

The Core Policy and Procedures Manual chapter on journal vouchers explains that “accounting transfers are recorded in the Corporate Accounting System by journal voucher. This provides the means for one ministry to charge-back another ministry for goods or services.”

This is where significant costs hide. If the AG’s office spends two years defending the province in a human rights case, those staff costs get billed internally to Education. But they never show up as “legal fees” in Education’s public budget documents—they’re absorbed into general operating costs or cost-sharing arrangements.

Example: The Ministry of Education spent roughly $2.6 million over 15 years fighting legal challenges from the BC Teachers’ Federation over class sizes and special needs funding. About $900,000 went to external lawyers; $1.7 million covered internal staff lawyers (Attorney General costs). Ultimately, the Supreme Court sided with the union—making the entire legal fight moot. But the $2.6 million was already spent and coded in the ledgers.

How payments get approved and recorded

No money moves without authorisation. The approval process varies depending on what’s being paid:

For Vendor Invoices (External Law Firms)

- 1. Division manager confirms expense (this legal work was authorised)

- 2. Finance reviews coding (correct ministry, STOB, program codes)

- 3. CFO or delegate approves (especially for large amounts)

- 4. Payment requisition created in CAS (using standardized forms)

- 5. Matched with invoice and paid via direct deposit or cheque

For settlements

Large settlements often require additional approval:

- Deputy Minister sign-off

- Attorney General consultation

- Risk Management Branch approval (for indemnities or significant claims)

The BC government’s risk management policies specify that “RMB approves indemnities, manages claims and litigation for many public sector agencies,” ensuring oversight of significant legal costs.

Once approved, the payment flows like any other—coded in CAS, matched to documentation, released to the claimant or their lawyer.

For Internal Transfers (Insurance Reimbursements, AG Billing)

When costs move between ministries or accounts—like a district reimbursing the SPP fund, or Education paying back the Attorney General—staff use journal vouchers. These internal transfers still require proper CAS coding: one account gets debited, another credited, with narrative explaining the purpose.

Every step generates a record. Every record has a code. Every code links back to a ministry, program, and expense type.

Real cases, real costs

These aren’t theoretical flows. Here’s what we know from public records:

- BC Teachers’ Federation legal battle (15 years):

- Total cost: $2.6 million

- External lawyers: $900,000

- Internal staff lawyers: $1.7 million

- Outcome: Supreme Court ruled against the government

- Result: Money spent, students didn’t benefit

- School District 57 sexual abuse settlement (2022):

- Amount: $1.1 million

- Source: District’s insurer (SPP)

- Context: Largest reported abuse settlement in BC history

- Hidden in: Insurance claims, not district operating budget

- Vancouver School Board legal costs (2023-25):

- 2023-24 actual spending: ~$3.2 million to one law firm (Harris & Company)

- 2024-25 budget allocation: $7.66 million for legal and litigation

- Includes: $3.5 million for one francophone school transfer case

- Context: VSB admits this is “one-time” cost that spiked the forecast—money that otherwise could fund classrooms

These examples share one pattern: the money ultimately came from education funding. Whether paid by ministry operating budgets, insurance premiums, or internal AG allocations, these dollars were not available for students.

Example flows

Accommodation denial Human Rights Tribunal case

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#008080', 'lineColor': '#000000'}}}%%

flowchart TD

A[Parent requests accommodation] --> B[District refuses or partially complies]

B --> C[Parent files Human Rights Complaint]

C --> D[Human Rights Tribunal process begins]

D --> E{Legal representation required?}

E -->|District hires lawyer| F[Direct Ministry Payment to Law Firm]

E -->|Ministry handles internally| G[Attorney General legal allocation]

D --> H{Settlement / Ruling?}

H -->|Settlement paid| I[Insurance / SPP fund pays district or claimant]

H -->|Ruling for parent| J[AG covers defence costs if appealed]

I --> K[District accounts for journal voucher / internal allocation]

J --> K

Family case money flow

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#008080', 'lineColor': '#000000'}}}%%

flowchart TD

%% Swimlane setup using subgraphs

subgraph Parent["Parent / Student"]

P1["Requests accommodation / reports incident"] --> P2["Files Human Rights Complaint or grievance"]

end

subgraph District["School District"]

D1["Receives request / incident report"] --> D2{"Handles internally or escalates?"}

D2 -->|Escalates| D3["Hires lawyer or notifies Ministry"]

D2 -->|Handles internally| D4["Attempts local resolution"]

end

subgraph Ministry_AG["Ministry / Attorney General / Risk Management"]

M1["Ministry authorizes payment"] --> M2["External legal fees processed via CAS"]

M2 --> M3["CFO signs off for large amounts"]

R1["SPP / Insurance assesses claim"] --> R2["Settlement or defence paid"]

AG1["AG staff handle internal legal work"] --> AG2["Internal cost allocation to Ministry recorded in CAS"]

end

%% Connections across lanes

P2 --> D2

D3 --> M1

D3 --> R1

M2 --> AG2

R2 --> AG2

Teacher / liability / workplace case

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#008080', 'lineColor': '#000000'}}}%%

flowchart TD

A["Event: Union grievance / workplace claim / student injury"] --> B["District notified"]

B --> C{Covered by insurance / SPP?}

C -->|Yes| D["SPP processes claim & pays settlement"]

C -->|No| E["District pays out of operating budget"]

D --> F["District records journal voucher / internal allocation"]

E --> F

B --> G{External legal counsel required?}

G -->|Yes| H["Direct Ministry Payment to Law Firm"]

G -->|No| I["Attorney General legal allocation"]

F --> J["Accounting completes CAS entry with STOB coding"]

H --> J

I --> JWhy the fragmentation matters

When advocates ask “How much does BC spend fighting families over special education?”, the government points to three different ledgers and claims ignorance:

- Ministry of Education says: “Legal costs are handled by the Attorney General and covered by insurance—we don’t track aggregate spending.”

- Risk Management Branch says: “We manage the insurance program, but case-specific costs are confidential and we don’t break down claims by dispute type.”

- Attorney General says: “We provide legal services to ministries but don’t itemize costs by subject matter—that’s administrative detail we don’t maintain.”

Each statement might technically be true within its silo. But collectively, they obscure a truth the system absolutely tracks: every payment was coded, approved, and recorded in CAS.

The fragmentation isn’t administrative accident. It’s designed opacity. By splitting costs across direct payments, insurance claims, and internal allocations—each managed by different branches with different reporting requirements—the province ensures no single entity can be asked for the total.

But the data exists. Finance processes the payments. Risk Management tracks the claims. The Attorney General bills the cost allocations. The numbers are in the system.

Streams of $$$ money

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#008080', 'lineColor': '#000000'}}}%%

flowchart LR

%% Layers

subgraph Direct_MoE[Direct Ministry Payments]

style Direct_MoE fill:none,stroke:none

A1["Lawyer retained by Ministry (e.g., Harris & Co)"] --> A2["Invoice processed via CAS / STOB 60/61"]

A2 --> A3["Payment approved by division manager / CFO"]

end

subgraph Insurance_SPP[Insurance / SPP Fund]

style Insurance_SPP fill:none,stroke:none

B1["Incident or Claim Occurs (student injury / accommodation)"] --> B2["District files claim with SPP"]

B2 --> B3["SPP assesses liability & processes payment"]

B3 --> B4["Journal voucher / internal allocation recorded in CAS"]

end

subgraph AG_Allocations[Attorney General Internal Allocation]

style AG_Allocations fill:none,stroke:none

C1["AG staff handle legal work internally"] --> C2["Costs billed to Ministry via internal allocation"]

C2 --> C3["Recorded in CAS under ministry program / STOB codes"]

end

%% Cross-stream connections (example of combined flows)

A3 -.-> B4

C3 -.-> B4

The cost of scarcity

These legal costs don’t exist in a vacuum. BC’s K-12 education budget has been squeezed for years, with per-student funding eroded by inflation and rising costs. That scarcity drives more conflicts, which drive more legal costs, which consume more scarce resources.

The cycle:

- Inadequate funding → Understaffed schools, insufficient supports, deferred maintenance

- More accidents, disputes, grievances → More liability claims and legal battles

- More legal costs → Less money for actual education

- Repeat

Vancouver School Board’s own materials acknowledge using “one-time funds” for costly legal battles while millions in special education funding sit unspent. Districts pay escalating insurance premiums while claiming they can’t afford accommodation. The province budgets for lawyers while eliminating teaching positions.

The money exists. It’s being spent to manage liability, not prevent harm. To defend exclusion, not provide inclusion.

The invisible cost: staff time enforcing scarcity

Legal bills and insurance claims tell only part of the story. The larger, hidden cost is staff labour—the thousands of hours spent by educators, administrators, and ministry officials managing conflicts that scarcity creates.

From a public administration perspective, the government absolutely knows:

- How much is paid to each law firm

- How much is charged through internal Attorney General allocations

- How much flows through insurance programs

- How much is coded to professional services

Treasury control, audit requirements, and Public Accounts all require that every dollar be coded, approved, and traceable. No ministry is allowed to spend money “without knowing.”

But can they know how much energy is being spent enforcing scarcity when you add up:

- All the hours spent by people making $200,000/year practicing ways to say “no” to families

- Or saying “yes, but” with accommodations that vanish within months

- The devastating impact on families who watch their disabled children fail, often having to withdraw them from school

- Parents sacrificing careers, marriages, and stability

They can count the hours. They just don’t call them “scarcity enforcement.”

Why staff time remains invisible

Staff time is tracked administratively:

- Salaries are budgeted

- Positions are classified

- Units report FTEs (full-time equivalents) and workloads

- Some functions track time allocation (especially legal, HR, finance)

But the system does not track purpose in a way that reveals harm.

No one codes their time as:

- “2.5 hours denying an accommodation”

- “1 hour reinforcing process over need”

- “3 meetings explaining why policy can’t flex”

Instead, it’s coded as:

- Case management

- Program administration

- Consultation

- Stakeholder engagement

- Compliance review

- Risk assessment

So yes—the energy is there. The labour is there. The cost is there.

What’s missing is the analytic frame that would let anyone see it as scarcity enforcement rather than normal operations.

Three structural reasons this cost stays hidden

It’s salaried time, not a transaction

Legal bills show up because money leaves the system. Staff time doesn’t trigger a payable—it’s already sunk. Once someone is hired, the system treats their time as “free” for any task within role scope.

That makes prolonged, process-heavy conflict perversely cheap on paper.

A family might spend three years fighting for accommodation. During that time:

- District special education coordinators attend dozens of meetings

- Principals write reports justifying denials

- School board lawyers review files

- Ministry officials provide “consultation”

- Risk management staff assess liability

All those hours cost money—salary, benefits, overhead. But because it’s internal labour, it never appears as a line item labeled “cost of fighting this family.”

Time tracking is coarse by design

Even where time tracking exists (legal services, some policy units), categories are broad:

- “File work”

- “Meetings”

- “Review”

- “Advice”

There’s no incentive—and often no permission—to log time by impact on families or preventability.

A ministry could track: “Hours spent on accommodation disputes that could have been resolved with earlier supports.” But that would require acknowledging that the work was avoidable—that inadequate funding created the conflict.

Measuring this would challenge policy neutrality

If a ministry ever produced a report saying: “We spent 18,000 staff hours last year managing accommodation disputes that could have been resolved with earlier supports”*—that would force uncomfortable questions:

- Why are staff being used as gatekeepers rather than problem-solvers?

- Is this workload evidence of underfunding rather than noncompliance?

- Are we optimizing for risk avoidance instead of outcomes?

So the metric never gets created.

The irony

From a systems perspective, staff time is often the largest hidden cost of scarcity:

- Repeated meetings with the same families, reviewing the same needs

- Duplicated documentation across multiple forms and processes

- Escalating chains of review (teacher → principal → district → ministry)

- Defensive decision-making that prioritizes liability over learning

- Emotional labour borne by frontline staff who see the harm but can’t fix it

Teachers, EAs, principals, district staff—they all absorb this load. And because it’s internal labour, the system treats it as neutral or unavoidable, rather than as a signal of dysfunction.

What could be estimated (but Isn’t)

Even without perfect data, government could approximate:

- Number of accommodation disputes per year

- Average staff involved per dispute

- Average hours per meeting × number of meetings

- Salary bands of participants

That’s basic workload analysis. Governments do this all the time for service planning.

The fact that it isn’t done or shared with the public is telling.

The real bottom line

The government cannot tell you how many hours were spent saying “no” to families.

Not because it’s unknowable.

But because the system was never designed to ask whether that work was necessary.

Legal bills leak through the cracks and become visible.

Staff labour disappears into normalcy.

And that’s exactly how manufactured scarcity sustains itself—quietly, politely, through meetings that look reasonable on paper and devastating in lived experience.

Scarcity isn’t enforced just with policy—it’s enforced with labour:

- People’s time

- People’s emotional energy

- People’s professional judgment constrained into compliance roles

That labour is real. It’s costly. It’s exhausting. And it diverts skilled educators and administrators away from solving problems toward managing them.

When we add up the legal fees, the insurance claims, the internal AG costs, and the invisible staff hours—the true cost of maintaining exclusion becomes staggering. And every dollar, every hour, represents a choice: invest in prevention and support, or spend it managing the consequences of scarcity.

What transparency would look like

By law, significant contracts and settlements should be publicly reported. The 2016 Open Government directive requires disclosure of all professional services contracts over $25,000, specifically listing “STOB 60 Professional Services: Operational & Regulatory” and “STOB 61 Professional Services: Advisory” as categories requiring disclosure. But it would take a very long time to piece the full cash cost of legal expenditures, which is likely the tip of the iceberg, when you add up staff time spent.

What should be readily available:

- Annual total legal services spending by ministry

- Breakdown by vendor (which law firms, how much)

- Insurance premiums and claims costs by category

- Settlement amounts (not case details, just totals)

- Cost allocation between ministries for shared legal work

What parents and advocates can demand:

- School boards itemizing legal and litigation costs in annual budgets (as Vancouver now does)

- Ministry budget books showing legal services as distinct line items

- Public Accounts providing ministry-level breakdowns for legal vendor payments

- Risk Management Branch publishing aggregate claims data by dispute type

- Routine FOI disclosure of financial administration records (not legal advice)

The Vancouver School Board’s explicit $7.66 million “legal and litigation” budget line is a transparency step worth replicating. Other districts and the ministry itself should follow.

Following the money

Understanding these flows matters for accountability. When district budgets are debated, when provincial estimates are tabled, when education advocates push for more resources—the question should be asked: “What are we spending on legal defence, and why?”

The answer reveals systemic priorities. A well-funded system would see legal disputes as rare exceptions. BC’s strained system treats them as inevitable operating costs—then obscures what those costs actually are.

Every parent group, teachers’ union, or education advocate can legitimately ask:

- What does our district spend on lawyers annually?

- How much goes to insurance premiums covering liability?

- What does the province spend defending policies that courts later overturn?

- Could that money have prevented the conflicts it’s now paying to manage?

Following the money through CAS, through Risk Management, through Attorney General cost allocations—this is how we hold the system accountable. Not to blame individuals, but to expose structural choices.

The government chose to spend $2.6 million fighting teachers over class sizes, then lost. The government chose to spend over $1 million fighting one family’s accommodation request instead of providing supports. School boards choose to budget millions for legal costs while leaving special education funds unspent.

These aren’t inevitable costs. They’re policy choices—made visible when we follow the money.

Where to look

For parents and advocates wanting to dig deeper:

- School board budget consultations: Ask what’s allocated for legal fees, insurance premiums, and settlement reserves. Request historical spending data.

- Public Accounts: BC publishes annual “Consolidated Revenue Fund Detailed Schedules of Payments” showing all suppliers paid over $25,000. Search for law firms, cross-reference amounts.

- Quarterly contract disclosures: ministries must publish contracts for professional services over $10,000. Check Ministry of Education disclosures—though notably, legal contracts often appear as “confidential legal services” with minimal detail.

- Freedom of Information requests: You have the right to request financial administration records. Ask for payment data (not legal advice), specify STOB codes, request aggregate totals if transaction detail is refused.

- District financial statements: Audited statements sometimes include notes about contingent liabilities, legal reserves, or significant settlements.

- Questions for candidates: During elections, ask what they’ll do about legal spending transparency. Request commitments to publish comprehensive legal cost reporting.

The information exists. The systems track it. The question is whether we demand access to what’s already being recorded—and whether we’re willing to ask why these costs keep growing while classroom resources keep shrinking.

The bottom line

British Columbia’s education system spends millions on legal defence and insurance every year. The exact total is obscured by fragmented accounting—split across ministry payments, insurance claims, and internal cost allocations. But every payment flows through the Corporate Accounting System, coded with vendor names, amounts, and dates.

The government tracks this information. It just doesn’t report it comprehensively.

When we follow the money, we find resources flowing toward managing crises rather than preventing them. Toward defending policies rather than improving them. Toward legal bills rather than learning supports.

These are choices, not inevitabilities. And transparency is the first step toward different choices.

Because every dollar spent on lawyers is a dollar that didn’t go to students. And British Columbia’s students deserve better than a system that budgets for litigation while claiming it can’t afford inclusion.

Want to understand what your district spends on legal costs? Start by asking at the next budget consultation. Want to know what the province spends defending education policies? File a Freedom of Information request for financial administration records. The money flows through traceable systems—we just have to follow it.