I have been watching the fallout from British Columbia’s new disability funding model unfold across social media for almost a week, and on Family Day, I am sitting down to reflect on what it means—not just this specific conflict, but the pattern it represents, the way these fractures keep regenerating despite sustained advocacy.

A note before you read this

I have watched the minister who implemented this policy ripped apart by parents critical of this change, accused of deliberate cruelty, where I see ideology and bureaucratic concessions. I am frightened of these parents organising in collective fury, as I can see how rage—however justified—can target individuals rather than systems. I have felt critical when the urgency of fighting for children who lost services leaves no space for celebrating families whose children finally gained access to support. I feel protective of our families who have fought so long for benefits and of the advocates who fought with them, often devoting their entire life to changing our system.

And yet, I’m one of these parents, who has been disenfranchised by this change.

This piece is my attempt to explain the pattern I keep seeing—not just in disability policy, but across every domain where communities are forced to compete for inadequate resources. The fracturing is predictable. The conflict is structural. And blaming individuals for operating inside systems designed to produce exactly these dynamics wastes energy we desperately need to conserve.

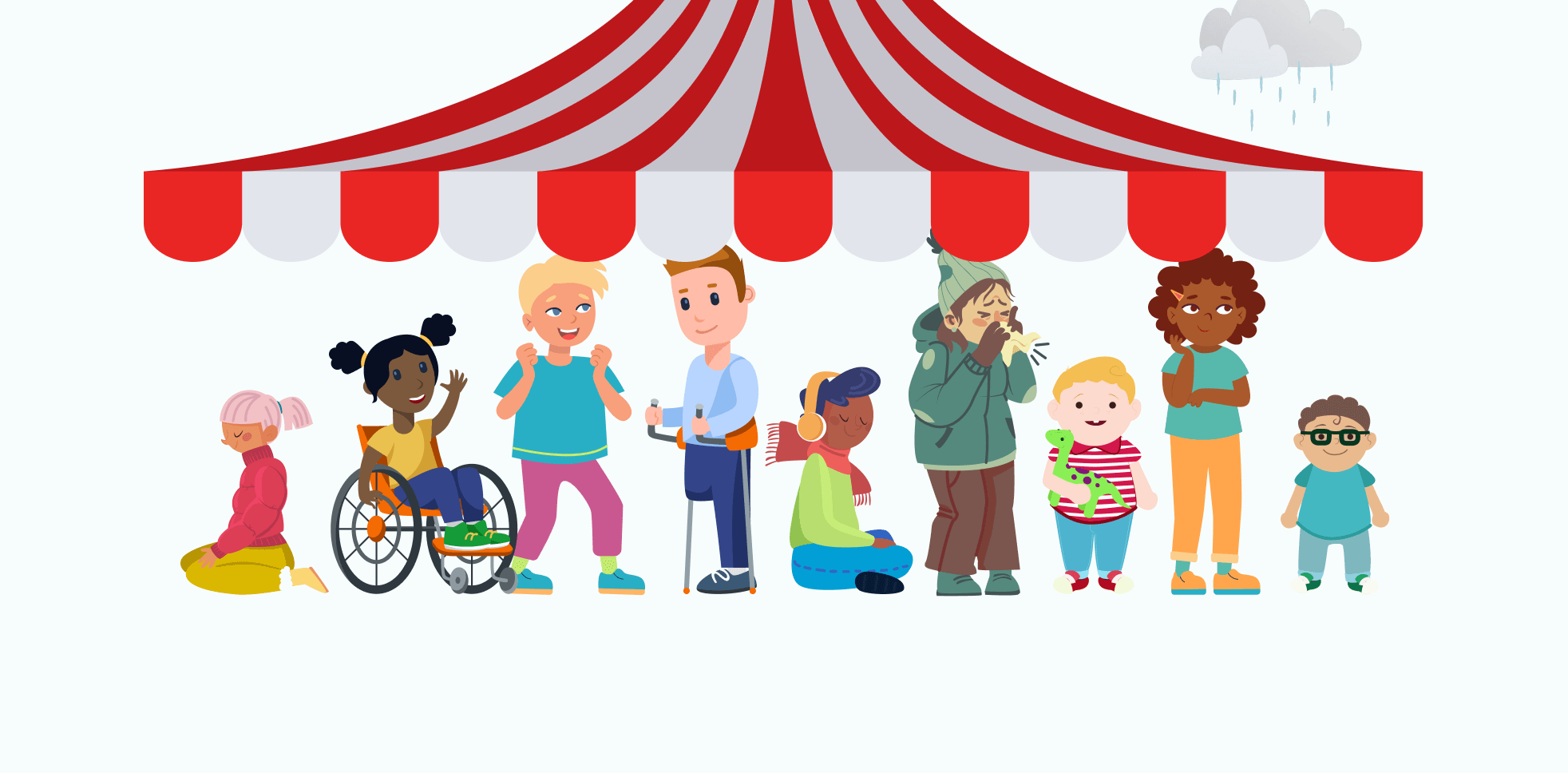

I am trying to name how scarcity ideology gets so deeply embedded that everyone involved—parents, advocates, bureaucrats, ministers—genuinely believes the tent must stay small, and how that belief keeps regenerating the same fights where people on all sides think they are doing the right thing while still producing harm.

This is not about taking sides. Seasoned advocates will keep being strategic because that is what works for them. Urgent parents will keep fighting loudly because their children are in crisis. Both are rational responses. Both create pressure in different ways. And understanding that—really understanding it—might at least help us stop wasting energy criticising each other for being exactly what the conditions we are in would predict.

Tensions grow

Four thousand three hundred and seventy one parents have signed a petition demanding reinstatement of the old funding guarantees. They are organising on a Discord server, speaking to media, fighting loudly for their children who are losing services under the policy implemented by the Ministry of Children and Family Development, which redistributes some support.

Initially, many established disability advocacy organisations celebrated the policy changes, calling it historic, applauding the province for expanding access. But as thousands of families began realising their children would lose services, the tone shifted—organisations began acknowledging the backlash, sharing parent testimonials about loss, recognising mixed feelings and uncertainty. And alongside that public shift, I sense frustration among some long-standing advocates toward these newly mobilising parents who appear not to understand what a significant victory this represents for many families, who seem unaware of the decades of labour that preceded them, who are mobilising in ways that potentially destabilise what was won or centre parental voices over disabled community voices, and who appear unwilling to leave space for the families gaining support to feel any joy.

This is not a new story. I have watched this exact dynamic unfold in environmental activism, in municipal politics, in healthcare reform, in every domain where scarcity forces communities to compete for inadequate resources. What I have learned is this: the conflict itself is structural and predictable. Seasoned advocates will always be strategic because strategy kept them effective inside systems that punish radical demands. New parents will always be urgent because their children are in crisis and they have not yet learned that the system treats urgency as illegitimate. Both responses are rational. Both are necessary. And criticising each other wastes the energy we need to push the levers that actually matter.

The deeper problem is not that people disagree about tactics or priorities. The deeper problem is that scarcity ideology has become so naturalised—so embedded in how we think about resources, about government capacity, about what is realistic or affordable—that everyone involved, including well-meaning people inside government, genuinely believes the tent must stay small. Expansion feels impossible. Asking for adequate funding for all disabled children feels naive, unrealistic, fiscally irresponsible. And so we fight over how to distribute inadequacy rather than organising to end it.

This is not conspiracy. This is ideology. And until we name it as such, we will keep tearing each other apart while the structural conditions that produce these conflicts remain untouched.

The government designed this conflict, but probably without malice

The Ministry of Children and Family Development restructured disability funding this year, moving from the old Autism Funding Unit model—which provided substantial support to autistic children but excluded many other disabled children—to a tiered system intended to expand access while managing costs. Some families gained support for the first time. Other families lost benefits their children depended on, or they were greatly reduced, or they might be the same, but more hoops to jump through were added. The government framed this as equity, as necessary rebalancing, as fiscal responsibility.

While the government make a significant investment, they also chose some redistribution. They could have added baseline funding for all disabled children and layered additional support on top for those with higher needs. They could have grandfathered existing services while building capacity for newly included families.

Instead, they built a system that inevitably turned families against each other—where some children could gain access only if others lost it, where the conflict we are witnessing now was baked into the policy design.

I do not believe this was malicious. I believe the people designing this policy genuinely thought they were making the best possible choice within the constraints they understood as real. I believe they absorbed the logic that adequate funding for all disabled children is unrealistic, unaffordable, politically impossible. I believe they thought redistribution was the only viable path toward greater equity. And I believe that belief itself is the problem—because it treats scarcity as a natural constraint rather than a political choice, and it makes harm inevitable by refusing to imagine expansion.

The conflict we are watching unfold was designed into the policy, but it was designed by people operating inside an ideological framework so pervasive they probably cannot see it as ideology at all. It just looks like fiscal responsibility. It just looks like the way things are.

Middle panel: Bigger tent, more kids under it – BUT two kids who were under the tent are now back in the rain

Bottom panel: What SHOULD happen – tent big enough for everyone

A note on numbers

The government has released some numbers indicating who will qualify for the supplement and the benefit, acknowledging that potentially five thousand families will lose some funding, but they have not released the baseline data that would allow meaningful comparison or assessment of the policy’s actual impact. Without knowing how many children currently receive AFU funding, what percentage will lose funding entirely versus receiving reduced amounts, what “less” actually means in concrete terms, or how many middle-income families face reduction or elimination of support, we cannot evaluate whether this redistribution achieves the equity the government claims or simply redistributes harm in ways that make it harder to track.

This absence of data serves no one well. While it shields the government from scrutiny over losses, it also allows both critics and supporters to inflate or minimise impact based on speculation rather than evidence. Responsible policy-making requires transparency. The government should release: how many children currently receive AFU funding, what percentage will lose all funding versus receiving reduced amounts, concrete definitions of what “less” means across different family circumstances, and how many middle-income families will be affected by the income-testing threshold. Until they do, we are all arguing in the dark about a policy that will fundamentally reshape support for thousands of disabled children.

A bit of history

In 2000, the BC Court of Appeal upheld an earlier ruling that the province had violated the Canadian Charter by denying treatment deemed medically necessary for autistic children. The lead plaintiffs—Michelle Auton, Sabrina Freeman, Leighton Lefaivre, Janet Gorden Pearce—were fighting for Applied Behavioural Analysis therapy for all autistic children. Not just the ones whose autism was “severe enough” to justify the expense. Not just the ones whose needs announced themselves in ways bureaucrats found legible. All of them.

The government wanted to ration care, to create tiers, to ensure that only the most visibly impaired children could access funding. The families refused. They organised across differences in their children’s presentations—bringing together families whose children had very different relationships to the label of autism, very different support needs, very different levels of functioning as institutions measured such things—and they insisted that all of them deserved support.

Viewed through today’s disability justice lens, where many autistic adults recognise ABA as compliance training that harms autistic children by forcing them to suppress their authentic selves, the intervention these families fought for is deeply troubling. But what was radical about their advocacy was not the specific therapy they demanded—it was their refusal to accept that disability could be divided into categories of deserving and undeserving, that only “severe enough” children merited support, that scarcity required hierarchy.

They won because they organised effectively, because they had resources to fight a Supreme Court battle, and because they made their demands impossible to ignore. The government eventually established the Autism Funding Unit, providing up to twenty-two thousand dollars annually for children under six and six thousand dollars for older children—for all autistic children, regardless of how “severe” bureaucrats judged their needs to be.

That victory was significant. It established a principle: that autism across varying presentations constitutes disability worthy of funding, that governments cannot simply ration support to the children whose needs look most dire. But the victory also created the conditions for the conflict we are witnessing now, because the families were not primarily fighting for universal disability rights—they were fighting for their own children’s access to a specific intervention. The principle they established applied to autism, not to all disabled children, and the substantial funding they secured came at a moment when other disabled children remained excluded entirely.

I am not saying they were wrong to fight for what they fought for. I am saying that advocacy under scarcity inevitably produces these partial wins that become the ground for future conflict—because when resources are inadequate, every victory for one group can be positioned as coming at the expense of another, and the government can use that positioning to avoid accountability for maintaining scarcity in the first place.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#21B25D', 'lineColor': '#21B25D', 'fontFamily':'Mulish' }}}%%

flowchart TB

S[System design under scarcity] --> O[Options presented as “realistic”]

O -->|Option 1| A[Save some now<br>Accept losses elsewhere]

O -->|Option 2| B[Refuse partial win<br>Risk near-total loss]

O -->|Option 3| C[Redistribution<br>Create winners + losers]

A --> R[Aftermath: accusations of complicity]

B --> R

C --> R

R --> K[Key point:<br>This is constrained choice,<br>not personal morality]

Parents fight for their children, and that is legitimate

I have not heard of a parent of a child with muscular dystrophy being told that they should be fighting for all neuromuscular conditions, or that their advocacy is selfish if it centres their child’s specific needs. I have not heard of parents fighting for cystic fibrosis research being told they are being exclusionary by not advocating equally for all respiratory conditions. People can fight for Type 1 diabetes funding without being accused of abandoning other endocrine disorders, can organise around childhood cancer without being expected to represent all pediatric illnesses, can push for better epilepsy support without hearing that they are being unfair to children with other neurological conditions.

But the mothers of autistic children are held to a different standard. They are expected to understand systemic inequality, to centre other disabled children’s needs alongside their own children’s, to fight for universal disability access rather than specific accommodations, and to gracefully accept policy changes that harm their children if those changes benefit other disabled children. They are told they are privileged when they fight for their own kids, naive when they do not immediately grasp the broader political landscape, exclusionary when they organise around autism rather than all disability.

This double standard exists because autism advocacy became large, visible, and successful. The mothers of autistic children organised effectively, secured significant funding, and built political power. And once they had won something, the expectation shifted: now they were supposed to be universal disability advocates, not parents fighting for their specific children’s needs. Now their wins could be positioned as coming at the expense of other disabled children, and their refusal to accept redistribution could be framed as selfishness rather than legitimate protection of their children’s supports.

But that expectation is absurd, and the critique itself is ideological. Parents organise around their children’s specific conditions because that is what parents do. The fact that autism parents did it effectively enough to win substantial funding does not mean they suddenly owe something different from what we expect of any other parents fighting for their children’s survival. The critique of them as privileged or exclusionary is a deflection—it allows the government to avoid accountability for creating scarcity in the first place, and it turns the fact of their earlier success into evidence of illegitimacy rather than proof that refusing the hierarchy actually works.

The four thousand parents mobilising now are fighting for their children. That is legitimate advocacy, regardless of how long they have been doing it, how sophisticated their political analysis is, or how well they understand the decades of work that came before them.

How we construct grievability

Judith Butler teaches us that whose lives are considered grievable—whose harm registers as loss worthy of collective response, whose suffering demands political action—is never natural or inevitable. Grievability is constructed through narrative, through systems of recognition that determine which lives matter and which can be sacrificed without moral consequence. When a life is rendered ungrievable, their death or harm does not count as violence requiring redress. They disappear from the moral calculus. The system can harm them without accountability, because their harm never registered as harm in the first place.

The disability hierarchy operates precisely through this mechanism of grievability. It determines whose needs are recognised as legitimate, whose struggles count as suffering, whose exclusion demands remedy. Children with profound intellectual disabilities, with visible physical impairments, with needs that announce themselves in ways legible to institutional systems—these children are grievable. Their harm matters. Their exclusion is recognised as injustice.

But concentrating the harm on level one and level two autistic families allows people to construct a narrative that makes the harm acceptable: these are wealthy families, affluent families, families with resources who can compensate through private therapy or advocacy or family support. These are families whose children’s needs are less severe, less real, more about parental anxiety than actual disability.

That narrative is false. Autism is evenly dispersed across the population—across class, across race, across geography. Level one and level two autistic children exist in poor families, in racialised families, in families without resources or capacity to fight. The parents most able to advocate from that community often come from a place of privilege because these are the parents with bandwidth to fight, but that does not mean they are wrong. And some of those families now losing services have no ability to compensate, no capacity to hire advocates or purchase private therapy, no safety net. They become ungrievable twice over: once because their children’s needs are dismissed as not severe enough, and again because the assumption is that families like theirs do not exist.

The people who accepted this redistribution believe they are righting a historical inequity—correcting an injustice where less severely disabled children received generous support while more severely disabled children were excluded entirely. From that perspective, removing funding from level one and level two autistic children is not harm—it is justice, rebalancing, taking back what should never have been given in the first place.

They say the most dire cases can follow the “needs-based pathway” for review. Meanwhile, many of these families have struggled significantly to advocate for their children in schools that have weaponised their children’s ability to mask, imposing that performance regardless of how much harm it causes. These parents are profoundly distrustful of complaints and review systems because they have been let down repeatedly—told their observations are anxiety, told their children’s distress is developmental, told that because their child can hold it together at school the harm they witness when their children fall apart after school is a parenting problem rather than evidence of inadequate accommodation. They have learned that systems designed to provide redress actually function to exhaust and delegitimise them, and they have no faith that a “needs-based pathway” will recognise their children’s needs any more accurately than the assessment systems that already failed them.

How professional advocacy becomes invested in access

Professional advocates learn how to navigate systems that resist change. They develop expertise in policy language, in legal frameworks, in the specific pressure points that make bureaucracies respond. They build relationships with people inside government, cultivate their reputation as reasonable partners rather than radical troublemakers, and over time they gain access—consultation roles, seats at policy development tables, credibility that makes their recommendations carry weight.

That access is real, and it often produces real gains. But it also creates investment. When you have spent years building relationships that allow you to influence policy, when your effectiveness depends on being seen as credible rather than extreme, when the children you serve depend on the incremental wins you can secure through strategic negotiation, you become protective of that access. You moderate your language. You fight for the gains that are possible. You frame demands in ways that sound reasonable to the bureaucrats you need to convince. You learn which battles you can win and which demands will only get you excluded from future conversations.

None of this is betrayal. It is adaptation to the conditions professional advocates work within. But it does mean that over time, the distance between what advocates publicly demand and what they may privately wish for grows wider. It means that when families experiencing acute harm show up demanding transformation, professional advocates often respond with frustration—not because they do not care about those families, but because they may understand those demands as naive, as politically impossible, as likely to destabilise the carefully negotiated gains that are protecting other children right now.

Some seasoned advocates watching this mobilisation unfold might reasonably ask: where were these parents when other disabled children were excluded? Why does the outrage only appear when their own children lose services? That frustration is legitimate. It reflects years of fighting for children who were invisible to a system that only recognised autism as worthy of funding. But that critique, however understandable, still operates within the framework scarcity creates—where this activism is treated as evidence of selfishness rather than as the predictable way parents organise around immediate need. The Auton families were not fighting for all disabled children either. They were fighting for autistic children, and they won a partial victory that excluded others. That is not because they were bad people—it is because advocacy under scarcity begins with the crisis in front of you, with the diagnosis your child has, with the leverage you can generate from your specific position.

How desperation produces tactics that look irresponsible but are actually rational

The parents mobilising now have not learned the careful language that makes professional advocates effective. They are demanding reinstatement of funding guarantees rather than negotiating for incremental improvements to the tiered model. They are speaking to media without coordinating their messaging. They are making noise in ways that some advocates worry could jeopardise the gains that were secured or alienate the government officials whose cooperation is necessary for future progress.

From the perspective of professional advocacy, these tactics look naive, counterproductive, potentially harmful. But from the perspective of parents whose children just lost essential services, these tactics are the only rational response available.

When your child is in crisis, careful planning feels like asking you to accept harm while you wait for conditions to improve. When the system has repeatedly told you that your observations are anxiety, that your child’s distress is developmental, that because your child can hold it together at school the suffering you witness at home must be a parenting failure, you stop trusting incremental processes that require faith in institutions that have already betrayed you. When you have spent years navigating bureaucracies that gaslight you, exhaust you, and ultimately deny your child the support they need, being told to moderate your demands and work collaboratively with government feels like being asked to participate in your own oppression.

Desperation produces innovation precisely because desperate people refuse constraints that professional advocates have learned to accept. They break etiquette. They make demands that sound unreasonable to people who understand what is politically possible. They organise rapidly and loudly in ways that bypass the careful relationship-building professional advocacy requires. And sometimes—not always, but sometimes—that refusal to accept what is supposedly realistic forces systems to shift in ways incremental advocacy never could.

This is how change has always happened. The Auton mothers were not professional advocates when they started fighting. They were parents whose children needed support, and they refused to accept that only some autistic children deserved funding. They made demands that sounded unreasonable to the bureaucrats managing scarce resources. They organised with enough force to make their demands impossible to ignore. And they won not because their tactics were professionally strategic, but because they refused the hierarchy that would have required them to accept that their children could be divided into deserving and undeserving.

The four thousand parents mobilising now are doing exactly what those mothers did. They are refusing to accept the redistribution framework. They are demanding that their children’s needs continue to be recognised as legitimate. They are fighting with the urgency that crisis produces. And yes, some of their tactics will be messy.

But you cannot stop people from fighting for their own children. And more importantly, attempting to do so wastes energy that should be directed at the government that created this conflict in the first place.

How scarcity ideology makes everyone believe the tent must be small

The deepest problem is not that parents and advocates disagree about tactics. The deepest problem is that scarcity thinking has become so naturalised that nearly everyone involved—parents, advocates, bureaucrats, policy designers, even ministers—genuinely believes that adequate funding for all disabled children is unrealistic, unaffordable, politically impossible.

This belief shows up in how people talk about the new funding model. Advocates who support the redistribution frame it as necessary fiscal management, as the only way to expand access given resource constraints, as choosing equity over maintaining privileged access for some children at the expense of others. Bureaucrats frame it as responsible stewardship, as ensuring sustainability, as making difficult but necessary choices. Even some parents who lost services accept the framing—their children’s needs are less severe, other children’s needs are more dire, maybe their children should not have been receiving so much support in the first place.

That acceptance is the result of decades of neoliberal governance that has made “we cannot afford to help everyone” sound like fiscal responsibility rather than political choice. It is the result of austerity frameworks that treat public resources as inherently limited rather than as collective decisions about how we allocate wealth. It is the result of policy discourses that frame expansion as naive, unrealistic, the domain of people who do not understand how government actually works.

But the scarcity itself is constructed. British Columbia is a wealthy province. The funding increase MCFD announced this year was significant—sixty-six per cent growth over previous budgets—which proves that expansion was always possible, that the previous constraints were choices, that when political pressure becomes impossible to ignore governments can find resources they previously claimed did not exist.

The problem is not that the province cannot afford to fund all disabled children adequately. The problem is that no one inside government has been required to demonstrate why adequate funding is impossible, to show the fiscal analysis that would justify redistribution over expansion, to prove that the administrative apparatus they are building to ration care costs less than simply meeting children’s needs would cost.

I believe—though the government has not released the analysis that would prove or disprove this—that funding every disabled child with a baseline amount and creating a transparent needs-based pathway for additional support would cost less than the system they built to assess, ration, deny, appeal, and defend. I believe that when you track costs across all ministries over time—the emergency room visits, the psychiatric hospitalisations, the family breakdowns, the school exclusions, the criminalisation of disability-related behaviours, the lifetime of income assistance—not funding disabled children adequately costs more than meeting their needs in the first place.

But as long as MCFD can make its own budget look sustainable by deflecting those costs to Health, to Education, to Justice, to Housing, the government has no incentive to do that analysis. And as long as everyone involved accepts that scarcity is real rather than constructed, we will keep fighting over how to distribute inadequacy instead of organising to end it.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#21B25D', 'lineColor': '#21B25D', 'fontFamily':'Mulish' }}}%%

flowchart TB

M[MCFD constrains direct supports<br/>Rationing and reductions]

H[Health absorbs crisis costs<br/>ER and mental health]

E[Education absorbs fallout<br/>Exclusions and unmet needs]

J[Justice absorbs fallout<br/>Criminalisation]

I[Income supports absorb strain<br/>Employment loss and poverty]

HO[Housing absorbs instability<br/>Family crisis]

V[Visible story<br/>Fiscal responsibility]

U[Hidden reality<br/>Costs paid elsewhere]

M --> H

M --> E

M --> J

M --> I

M --> HO

M --> V

H --> U

E --> U

J --> U

I --> U

HO --> U

Understanding the pattern: different advocacy, different pressure

The current conflict is predictable and structural. Seasoned advocates will be strategic because strategy is what kept them effective. New parents will be urgent because their children are in crisis. Both responses are rational. Criticising each other for acting exactly as our conditions would predict wastes the energy we need to push the levers that actually matter.

Seasoned advocates carry crucial knowledge—about what pressure points make bureaucracies shift, about how policy language works, about which legal frameworks create accountability, about the history of wins and losses that shape current possibilities. New parents carry urgency, energy, and the willingness to make demands that sound unreasonable to people who have learned what is supposedly realistic. Both create pressure. Both matter. And understanding that—really understanding it—might at least help us stop wasting energy criticising each other for being exactly what we are.

The system of scarcity benefits when we fracture. When we spend energy debating whose child is really disabled, whose needs are most severe, whose advocacy is most legitimate, we waste energy. When we attack each other for being exactly what we are—when advocates are called complicit for accepting incremental gains, when desperate parents are called naive for refusing to moderate their demands—we let time pass where we are not pushing for the new policy to be refined in ways that address inadequacies.

Every type of advocacy plays a role in forcing change. Strategic negotiation secures incremental wins that protect some children right now. Urgent mobilisation threatens the government’s ability to maintain scarcity. Legal pressure through tribunal complaints creates accountability. Fiscal analysis makes expansion arguments impossible to ignore. Media campaigns make silence politically untenable. None of these tactics work in isolation, and all of them create pressure in different ways.

What matters is not that we all agree on tactics or priorities. What matters is that we stop treating different approaches as betrayals, that we recognise the pattern for what it is—structural and predictable—and that we direct our fury at the ideology that makes scarcity feel inevitable rather than at each other for responding to that scarcity in different ways.

The levers that actually matter

If we want to force the government to expand rather than redistribute, there are specific levers we can push.

- Flood the tribunal. I filed human rights complaints for both of my children this week. Thousands of families could do the same. When the BC Human Rights Tribunal receives enough complaints documenting that the policy causes harm, that the implementation violates rights, that the assessment process fails to recognise children’s needs, that becomes evidence of systemic failure that is much harder for government to dismiss than individual stories.

- Build the fiscal case. The government has not released analysis showing that redistribution costs less than expansion. We can build that analysis ourselves—documenting the deflected costs to Health, Education, Justice, Housing, calculating the administrative expense of assessing, denying, appealing, defending, demonstrating that adequate funding for all disabled children would likely cost less than managing the conflict this policy produces.

- Push for specific policy flexes. Reversing the entire restructuring is probably unrealistic at this point. But expanding who qualifies for higher tiers, improving the needs-based pathway, increasing baseline funding amounts, reducing bureaucratic barriers, grandfathering families who were receiving higher amounts—those changes are achievable if we organise strategically around them rather than spending energy fighting each other.

- Refuse the hierarchy. Every time someone suggests that level one or level two autistic children’s needs are less real, less severe, less worthy of support—every time someone accepts the framing that some children must lose services so others can gain them—that reinforces scarcity logic. We need to keep saying: all disabled children deserve adequate support, equity requires expansion, redistribution under scarcity is harm no matter how you frame it.

- Name the ideology. The belief that we cannot afford to help everyone is political, not fiscal. Calling it out as such—over and over, in every conversation, in every organising space—makes it visible as choice rather than constraint.

The theft of joy

The system grants so little relief to families with disabled children that when some families finally gain access to support they desperately needed, their moment of hope feels fragile, precious, requiring protection. But protection from what? From other families’ grief? From the political reality that their gain came through redistribution rather than expansion? From the accusation that their celebration is complicity in someone else’s loss?

These families have waited years for recognition, for resources, for any acknowledgement that their children’s needs matter. They have navigated systems that excluded them, fought for assessments that kept finding their children ineligible, watched other families receive substantial support while their own children received nothing. And now, finally, there is funding. Finally, their children can access therapy, support, services that might actually help. That joy is real. That relief is legitimate. And the fact that it arrived through a policy that harmed other families does not make their celebration wrong—it makes the policy wrong.

But families whose children lost services are being asked to hold space for that joy while their own children are in crisis, while services they depended on disappear, while the system that finally recognised some children as worthy of support did so by rendering their children newly ungrievable. They are supposed to be happy that equity expanded even though their child became the price of that expansion. They are supposed to celebrate progress even as they experience it as devastation.

Both positions are completely rational. Both are evidence of how little this system allows anyone to have.

When resources are adequate, one family’s gain does not require another family’s loss. When the tent is big enough, celebration does not feel like theft. When support is universal rather than rationed, joy stops being competitive. But under scarcity, even relief becomes something we fight over—where holding space for someone else’s hope feels like betraying your own child’s suffering, where protecting your own moment of celebration requires dismissing someone else’s grief as privileged or naive or insufficiently grateful for what was secured.

The fact that we are fighting over who gets to experience joy, over whether relief can be celebrated when others are losing ground, over whose hope is legitimate and whose pain deserves recognition—that itself is evidence of how brutal the system is to all of us. Scarcity does not just limit resources. It poisons the possibility of shared celebration. It turns every win into evidence that someone else lost. It makes even joy feel like complicity.

This is what ideology does. It makes us police each other’s moments of hope because we have learned that there will never be enough, that someone must always lose for anyone to gain. And until we name that belief as constructed rather than inevitable, we will keep tearing each other apart over scraps of relief that should never have been scarce in the first place.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#21B25D', 'lineColor': '#21B25D', 'fontFamily':'Mulish' }}}%%

flowchart TB

S[Scarcity environment<br/>Support is never enough]

N[Policy change distributes relief unevenly]

J[Relief for newly included families]

G[Loss for families losing supports]

C[Relief feels fragile<br/>Loss feels urgent]

T[Feelings get moralised<br/>Joy seen as complicity<br/>Grief seen as selfishness]

U[Outcome<br/>People police each other<br/>Demand for expansion weakens]

S --> N

N --> J

N --> G

J --> C

G --> C

C --> T

T --> U

What I am asking

I am not asking anyone to be quiet. I am not asking parents to accept harm. I am not asking advocates to stop fighting for what they believe their children need.

I am asking us to direct our fury a little. The people who came before you—the advocates who fought for years to secure any funding at all, who built infrastructure you are now using—they are not your enemy. The families that are celebrating that their children can have therapy finally—they are not your enemy. The people mobilising now—the parents reacting to real harm, demanding that their children’s needs be recognised—they are not your enemy either.

The scarcity ideology that makes adequate funding for all disabled children sound unrealistic is the target. The policy framework that forces families to compete for inadequate resources is the target.

Refuse the hierarchy. Name the ideology. Build the case for expansion. Push the levers that create pressure.

We are strongest when we refuse to accept that the tent must stay small, when we stop tearing each other apart over who deserves relief, when we make demands that sound impossible until we make them inevitable.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#f0ffff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#21B25D', 'lineColor': '#21B25D', 'fontFamily':'Mulish' }}}%%

flowchart LR

A1[Strategic advocacy<br/>Consultation and policy work]

A2[Incremental gains<br/>Protection for some children]

B1[Urgent mobilisation<br/>Petitions and media]

B2[Disruption of normal process<br/>Public pressure]

C1[Legal accountability<br/>Tribunal and complaints]

C2[Rights violations documented]

D1[Fiscal pressure<br/>Cross ministry costs]

D2[Scarcity challenged as choice]

E[Combined pressure<br/>Multiple forces at once]

O[Most likely outcome<br/>Policy flex and expansion]

A1 --> A2 --> E

B1 --> B2 --> E

C1 --> C2 --> E

D1 --> D2 --> E

E --> O